In our first article on Compositional Network Architecture, we emphasized its value as a descriptive model. This article considers its uses as a prescriptive model of network architecture.

As a prescriptive model, the goal of CNA is to allow maximum design freedom inside networks (the modules in our architecture), while ensuring that networks of all designs are composable. In keeping with this goal, the formal semantics of CNA (in Alloy) constrains intra-network mechanisms such as session protocols and routing loosely, requiring only certain data in the network state. The operators for network composition, on the other hand, are formalized completely.

The semantics of a network is expressed in terms of reachability, and the semantics of a composition operator defines reachability in a composition of multiple networks. Reachability represents both end-to-end and path properties, which are frequently important for security (see below). Reachability is defined at the granularity of packet headers, so it encompasses session properties. There is a form of reachability dependent only on infrastructure (what the network “is willing” to do), and another form that includes a traffic model (what the users want the network to do). Comparing these, it is possible to verify that a network satisfies all legitimate user requirements.

To realize the benefits of composability, networks should be built with external interfaces that conform recognizably to CNA. With such networks, composition can be implemented automatically and verified correct simply by checking known consistency properties at the interfaces. We now have an implementation of CNA composition in P4 [1], and are using it to explore the benefits of composability in building networks with programmable data planes. These benefits include implementation reuse and–most interesting to the readers of this site–easier verification.

The Alloy model of networking (on which the semantics is based) can be used as a tool for describing classes of networks and verifying their properties. In parallel with implementation activities, experiments with Alloy modeling and verification are yielding many insights into modular verification of networks. Some of these insights are summarized below.

Modular Verification of Layered Networks

From one perspective, layering is “just tunneling.” It’s true that an overlay link is implemented by an underlay session with the mechanisms of encapsulation and decapsulation, but this reductive view misses a major truth about verification: The whole overlay network matters, because it is the whole overlay network that defines the purposes, properties, and packet traffic of its links, while the links just happen to be implemented as tunnels in some other network.

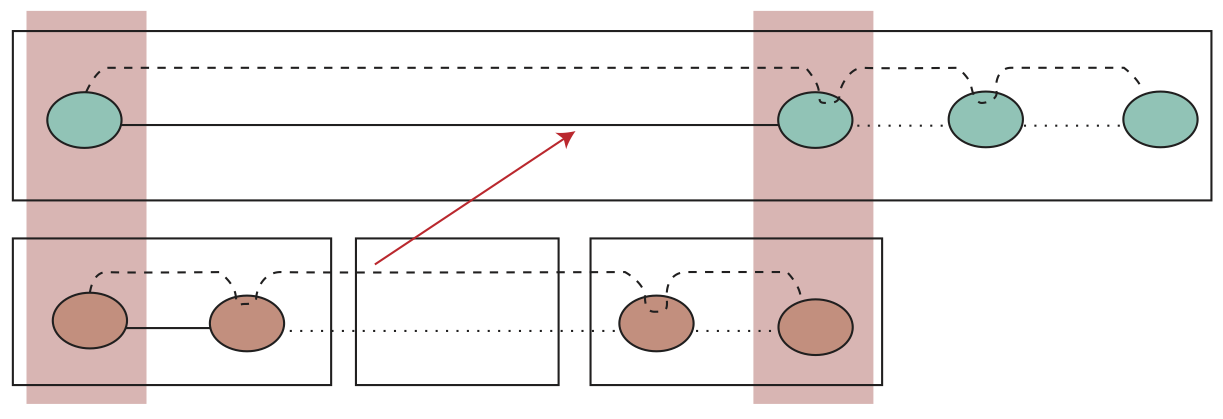

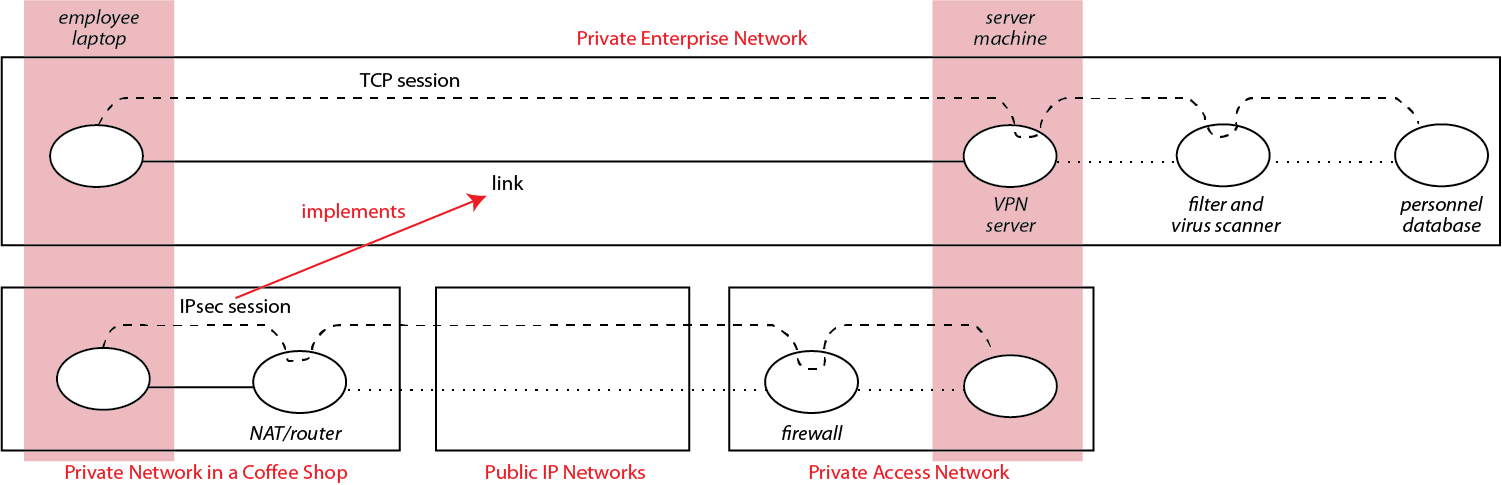

To see how this works, we have investigated numerous examples in which IP networks offering enhanced services are layered on the bridged IP networks of the public Internet. The figure shows an example, a Virtual Private Network, from [1]. The enhanced services of the VPN ensure a variety of security properties. Other examples explore correctness properties for multicast, mobility, and reliability services.

In all these examples, layering enables very successful modularity in verification. In fact, in these experiments every property I looked at could be proved exclusively in one network or the other. These properties fall into two categories, in a roughly even split:

-

Because layering enforces a separation of concerns, some properties only need to hold in one network.

-

Some properties are hierarchical. It is required or assumed that they are true of the links of an overlay network. To satisfy this requirement or support this assumption, they must be true of the underlay sessions that implement these links. As a result, they are proved in the underlay network and used as axioms in the verification of the overlay network.

Verifying one layer/network at a time is much easier than verifying their composition as one monolithic network, for three major reasons:

-

Each network is smaller! One usually has fewer nodes than the other, and in the nodes common to both networks the forwarding rules of the monolithic version will be partitioned between the two layers. Sometimes the benefit of modularity is even greater, because the number of forwarding rules in the monolithic version is the product of the number of rules in modular layers.

-

Each network is more focused and specialized, and has more structure that can be exploited by verification. As a simple example, consider the VPN. An employee of the enterprise is in a coffee shop, with laptop connected to the Internet through WiFi. Its Internet address is in the coffee shop’s block, and is largely meaningless for filtering. At the same time, in the overlay VPN, it has an authenticated IP address that indicates the employee’s department, rank, and access privileges. As a result, filtering in the VPN, based on source IP address, can have pinpoint precision.

-

There is no need whatsoever to verify the composition of the networks, which might be buried in the details of the monolithic version. In the modular version, layering composition is performed by a verified operator with well-known properties. As an important bonus, network forwarding never alters packets, so invariant forwarding can be used as an axiom in intra-network verification. Invariant forwarding holds because a router’s usual functions of adding/deleting headers and changing header fields are all subsumed by the layering operator, and are viewed as part of composition.

A short paper on network verification [1] uses the the VPN example to explain how a number of security properties could be verified. This verification can take advantage of many existing tools for network verification, as most of the properties are familiar combinations of filtering and forwarding properties in IP networks. Verification also combines results from different proof techniques, as follows: First, mathematical proofs establish the properties of cryptographic session protocols. These session protocols implement secure overlay links. Next, path analysis in the overlay verifies that a designated path through the network consists of only secure links and trusted nodes.

A Subtle Form of Layering: Subduction

In CNA, subduction is a third network-composition operator. It is a combination of bridging and layering, with an extra verification condition to make it work as expected. Although subduction may be new as a concept, it is common in networking. Roughly speaking, pure layering on the public Internet requires the participation of both session endpoints (as in the VPN example). Whenever one or both endpoints does not participate in the overlay, there is likely to be subduction. So it usually occurs whenever a special-purpose IP network is bridged with the public Internet, because only one endpoint is a user of the special-purpose network.

(For the curious, “subduction” is a geological term. Find a picture, and you will see that one tectonic plate both abuts and slides under another plate, just as the public Internet is bridged with a special-purpose network, and also implements its links by means of layering.)

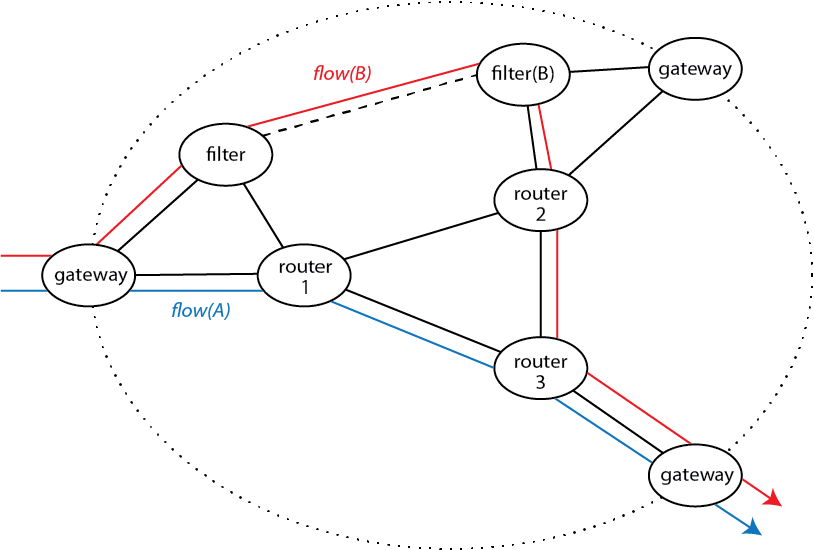

In our work with the P4 implementation of CNA, one case study includes some network services requiring flow affinity–all the packets of a designated flow must pass through a single stateful filter. For example, in the figure below, the blue packet in flow(A) does not require flow affinity, and it is simply routed through the network from one gateway to another. The red packet, in contrast, is in flow(B) and needs to pass through the filter filter(B). Both packets enter and leave the network at the same gateways, and we do not want the difficulty of altering normal routing to include location-dependent filtering. To keep the enforcement of flow affinity independent of normal routing, we implement it as an overlay with subduction. In this figure, the solid black lines are physical links, while the dashed black line is a virtual overlay link.

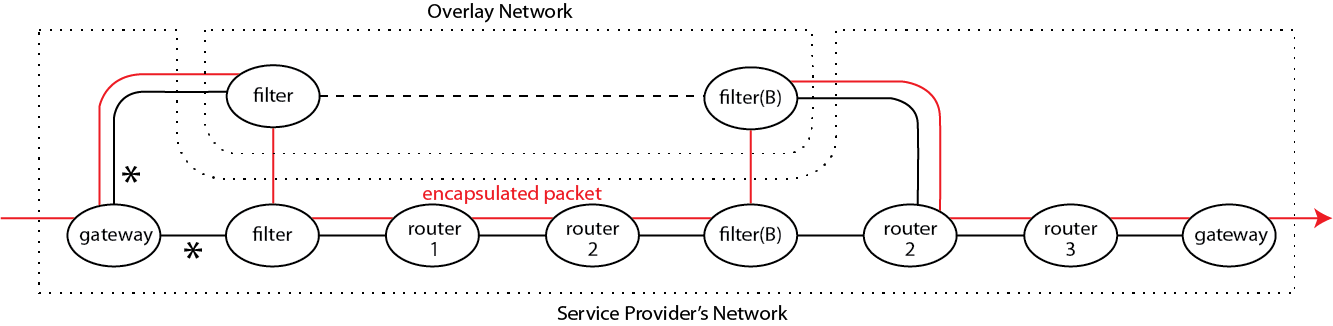

The figure below shows the architecture of this solution, superimposed on the physical path of a packet in flow(B). It enters the overlay through a bridging link from gateway to filter. In the overlay, it is routed to the filter responsible for flow(B). As it travels on a virtual link through the overlay, it is also traveling through the physical links of the underlay, because the overlay is layered on it. The packet exits the overlay through a bridging link from filter(B) to router2.

There is a fair amount of detail to be managed for the bridging and layering to work right, but this detail is all supplied automatically by our composition operators. There is also an extra constraint because of the subtlety of subduction–the two links marked with asterisks are exactly the same physical link, connecting gateway and filter machines. The two “filters” are members of different networks on the same machine, again implemented automatically by our P4 mechanisms.

Finally we can get to the topic of verification! Working with models of a flow-affinity-preserving network, a general network, and subduction, I have found a set of constraints on the general network that guarantee correctness. Here correctness consists of two properties:

-

The overlay and general network, composed by subduction, enforce flow affinity on all selected flows.

-

If the overlay has no other added functions (e.g., it does not filter packets), end-to-end reachability in the composed networks is exactly the same as in the original general network.

In practice the overlay will have added functions and will alter reachability, but the flow-affinity mechanism itself should be neutral.

The result is a theorem that if a general network satisfies the constraints, then its composition with the overlay has the specified properties. These constraints are not easy find. Yet once we know what they are, they make sense and are satisfied by normal networks. Then, with only these known constraints to check, verified session affinity can be added painlessly to most networks.

Correctness of a flow-affinity overlay is not something to be verified on a real network–it is far too complex, and even if it were accomplished, the effort that went into the proof could not be reused. As this example shows, the sensible approach is to prove the theorem with an abstract model, then verify that the real network satisfies the straightforward assumptions in the proof.

Network Properties

In summary, the common theme of these verification experiments is that they reveal a much richer set of network properties than usually seen in the literature on network verification. This is because the structure and modularity of CNA make it possible to get closer to the purposes and specializations of each network, without having them obscured by the overall complexity of a set of composed networks. Access to this kind of design detail provides understanding, not only of the many properties that make designs work, but also of the practical constraints that make the properties hold.

[1] Pamela Zave, Jennifer Rexford, John Sonchack, “The remaining improbable: Toward verifiable network services,” https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.12861, 2020.

Pamela Zave

Pamela Zave