Compositional Network Architecture is a new descriptive model of networking, possibly the first since the “classic” Internet architecture of the late 1980s. You all know the classic architecture: it has physical, link, network, transport, and application layers.

This article will talk about two reasons why CNA is worth your attention:

- It provides precise and comprehensive descriptions of how the Internet works today. In doing so, it solves a mystery of Internet evolution.

- It helps us identify recurring patterns in networking. These are problems that occur in many different, but predictable, contexts, along with a range of solutions to them. We are so excited about this way of teaching networking that we are writing a textbook based on it.

A third reason, modular verification, is the most relevant to this site, so it will be covered in a follow-up article.

Describing today’s Internet

CNA is different from the “classic” model of Internet architecture in several important ways, but in this article we’ll talk about just one: the definition of layering.

Layering in the classic model is layering in the ordinary software-engineering sense: the overlay depends on the underlay, while the underlay is independent of the overlay and incorporates no knowledge of it. There is a fixed number of layers, each with a different function to perform. Just as each layer can be completely different from the others, the interface between two adjacent layers can be different from other interfaces.

CNA, on the other hand, is based on the idea that the module of networking is a network. Each network is a microcosm of networking, with all the basic mechanisms including a namespace, nodes, links, routing, forwarding, session protocols, and directories (although some parts can be vestigial in some networks). In this model the Internet is a flexible composition of many networks; these networks differ from each other in purpose, geographical span, membership scope, and level of abstraction. Networks are composed with two operators, bridging (with the obvious meaning) and layering.

In any network, a session is an instance of one of the services provided by that network. At a minimum, it is a set of packets that network users group together. According to the CNA definition of layering, one network is layered on another network if a link in the overlay network is implemented by a session in the underlay network. This means that the overlay link is virtual, while the links in the underlay network can be virtual or physical.

As a consequence, layers in the new model are bigger than layers in the classic Internet architecture–for example, the classic network and transport layers of the Internet together make one CNA layer composed of IP networks bridged together. The advantage is that a bigger module is more complete, so a network’s interface to an overlay network is the same as the interface of an underlay network to it. In other words, we have made networks composable like Lego bricks.

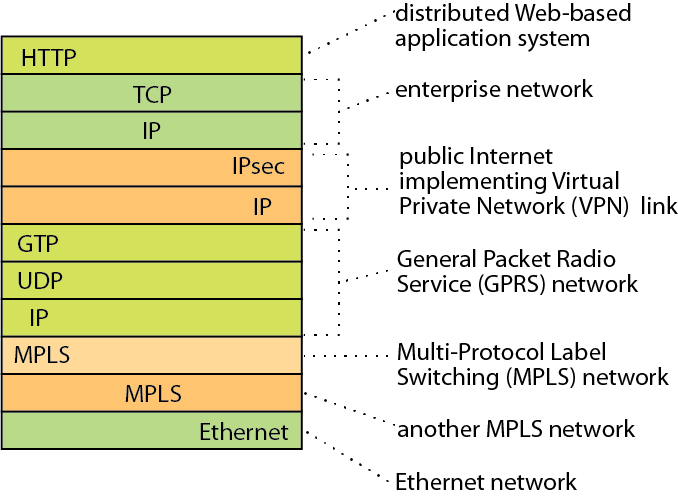

The picture shows the headers of a typical packet in the AT&T backbone network. The packet is traveling through 6 layered networks simultaneously, 3 of which are IP networks. Each IP network is revealed by an IP header for forwarding and one or more session-protocol headers.

At other observation points, packets would likely have similar complexity, but with different layers, because there is no need for global agreement on compositional architecture. As explained in detail in our Communications of the ACM paper [1], this and many other observations solve a mystery of Internet evolution: how the Internet has evolved since 1993 to meet many difficult new challenges, despite the fact that there has been no major change in the IP protocol since then.

Patterns in networking

Because CNA defines many ways in which all networks and network interfaces are similar, it also points to problems that most networks or compositions of networks will have to solve. The word is “most” rather than “all” because the restricted purposes of some networks, or the extra similarities between some composed networks, can simplify some problems out of existence.

Viewed with enough abstraction, each predictable problem has a suite of common solutions. The problem and the solutions make a recurring pattern. Teaching these patterns seems much more meaningful and memorable than teaching detailed instances of the patterns without linking them together. We are so excited about this way of teaching networking that we are writing a textbook based on it.

On the way, we have written two survey articles based on CNA, which will become chapters of the textbook.

Mobility is the network function that maintains network connectivity to a machine, despite the fact that the machine is moving its attachment to the network. “The design space of network mobility” [2] explains that there are exactly two patterns for providing mobility.

- In one pattern, the named machine simply moves from one access link of the network to another, and routing is updated dynamically so that the machine can still be reached under the same name. For example, MAC learning in an Ethernet can find a machine by its MAC address after it has moved.

- In the other pattern, layering is involved. The mobile machine retains its name and links in the overlay, despite the fact that it is moving. In the underlay network that is implementing these links, the mobile machine has a location-dependent name, which necessarily changes as it moves. The session protocol implementing an overlay link signals the change from one session endpoint to the other, so that the stable endpoint starts sending session packets to the new name. Most proposals for adding mobility to IP networks use this pattern.

These patterns had never been recognized before our paper, and it was CNA that enabled us to see them.

Our other survey article takes on the subject of network security [3]. It illustrates an extremely important point, which is that CNA-based teaching of networking offers a solution to an otherwise insoluble problem, which is the explosion of topics to be covered in a networking course. The paper frames the subject of network security, presents a practical classification of security attacks, and divides all defense mechanisms into four patterns. We have planned a tutorial on this material, covering the patterns in 3 hours of lecturing. The same lectures would work in a networking course, especially supplemented by reading the article. The students might not get all the details, but they would have an easy-to-remember framework in which to fit any new security attack or defense they encounter.

[1] Pamela Zave and Jennifer Rexford, “The compositional architecture of the Internet,” Communications of the ACM 62(3):78-87, March 2019 (http://www.pamelazave.com/cnaCACM19.pdf).

[2] Pamela Zave and Jennifer Rexford, “The design space of network mobility,” Olivier Bonaventure and Hamed Haddadi, editors, Recent Advances in Networking (http://www.sigcomm.org/content/ebook/SIGCOMMeBook2013v1_chapter8.pdf), ACM SIGCOMM, 2013.

[3] Pamela Zave and Jennifer Rexford, “Patterns and interactions in network security,” ACM Computing Surveys 53(6):118, 2020, to appear. A version with more explanation, examples, and references is available at https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.13371.

Pamela Zave

Pamela Zave  Jennifer Rexford

Jennifer Rexford