James Carville coined the phrase “It’s the economy, stupid” to say that what mattered in an election year was the economy. Formal methods search through vast state spaces in reasonable time by automatically finding (often implicit) equivalence classes of the state space, or by exploiting modularity or abstraction. But for some domains like networking, it appears better to precompute the equivalence classes before verification explicitly. Let me develop this idea in this post, targeted to networking folks not familiar with formal methods and to formal methods folks not familiar with networking.

For networking readers, formal methods treat a system as a mathematical object. We then prove (i.e., by covering all cases) that some property holds. For example: “source $S$ cannot send a packet to destination $D$ over any path” to enforce security. While the classical way (Floyd-Hoare) was to write proofs or (recently) use proof assistants like Coq (which require human ingenuity), I will concentrate on algorithmic search techniques that are more “turnkey” for network operators.

Algorithmic search methods search across the entire state space to verify a property. They include tools like SAT solvers, model checkers, and symbolic execution systems. All have found success in networks. And yet to scale to say a large data center network, these classical tools have to be modified to work, grouping the state space into sets.

I start my network verification class by giving some idea of the state space for the $S$ to $D$ reachability problem. Assume that the only header fields that matter for forwarding are the destination and source IP address, and the TCP destination and source ports (used in Access Control Lists). Assuming IPv4, that gives $32 + 32 + 16 + 16 = 96$ bits. Thus the state space is more than $2^{96}$, which seems astronomical. How in the world – I ask them – can we search through this large state space in reasonable time?

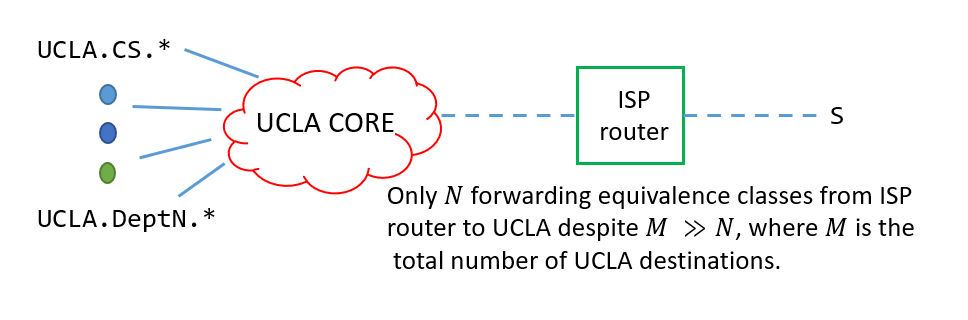

Having puzzled them, I then ask them whether to figure out how packets go to UCLA from an ISP do we have to consider all possible UCLA IP addresses?

The lights come on as they realize that it is possible to “compress” say all $\texttt{UCLA}/16$ ($128.16.*$) into one equivalence class.

As the packets come closer to UCLA, the equivalence classes may change to the departments (see Figure).

Of course, it’s more complicated than simply writing down the department names because of ACLs and the fact that different routers may “see” different equivalence classes.

But the basic intuition is sound.

The first generation of network verification tools reduced network verification to classical verification tools. For example, Anteater from UIUC reduced its reachability to a SAT formula, and Flowchecker from UNC reduced its reachability to model checking. Intuitively, reachability can be expressed as a Boolean formula assuming finite paths because a packet can reach from $S$ to $D$ if for some path $P$ (the OR of all paths from $S$ to $D$) all the routers in $P$ forward the packet to the next router (AND across all routers). Classical tools also scale by working symbolically in terms of sets of states.

Consider a SAT formula: $S = (a \land b) \lor (c \land d)$, where $a$, $b$, $c$, and $d$, are boolean variables that can be set to true or false. Is there some assignment of truth values to $a$, $b$, $c$, and $d$ such that S is true? The DPLL search procedure uses a search tree that branches on variable values. After branching on $a$ and $b$, the procedure can conclude that the formula is satisfiable $(a = \mathtt{True}, b = \mathtt{True})$ without considering $c$ or $d$. Thus a SAT solver works symbolically in terms of sets of states. Modern SAT solvers use CDCL-based algorithms with clause learning (which essentially learns implicit equivalences automatically).

Similarly, model checkers today are symbolic – they work with sets of states. For example, when a model checker considers a program line $“\mathtt{If}\ x < 9\ \mathtt{then}\ a = 5\ \mathtt{else}\ a = 10”$, it does not search through all possible values of $x$, but considers a tree that branches on the value of the Boolean formula $(x < 9)$. Unfortunately, both Anteater (based on SAT) and Flowchecker (based on model checking) did not scale to large networks. I conjecture this is because the sets computed do not naturally align with the natural equivalence classes for networking (e.g., $\mathtt{UCLA}.*$ that my students intuitively grasped).

I became an accidental tourist in the world of formal methods when I did a sabbatical at Stanford visiting my friend Nick McKeown in 2004. Nick’s student Peyman Kazemian had invented a ternary algebra for reasoning about shared SDN networks. We persuaded Peyman to apply it to general IP networks (SDN wasn’t fashionable yet) to compute tasks like packet reachability and loops. We were clueless about existing work like Anteater and FlowChecker.

The ternary algebra (where a bit could be either a $1$, $0$ or the wildcard character $*$) could easily model prefix and packet classification rules. But it could also model a set of packets moving through the network, in the same way, an equivalence class, as a wild card expression. For example, all packets destined to UCLA from an ISP would be a single wildcard expression. Note that equivalence classes are sets as in symbolic reasoning but are sets defined by an equivalence (symmetric, transitive, reflexive) relation, so there is a bit more structure.

While this technique, which we called Header Space Analysis, was elegant, we found it was as slow as a tortoise. The header expressions were breaking into too many pieces as the tool hauled them through the network. In other words, the equivalence classes were fragmenting unnecessarily. Consider a router contained two rules matching the destination address $1*$ and $11*$ (analogous to $\mathtt{UCLA}.*$ and $\mathtt{UCLA.CS}.*$). The classes that matched $11*$ and not $1*$ (IP does longest matching prefix) were being split into $2^{31}$ pieces.

So we tried representing wildcard expressions as subtractions (e.g., $\mathtt{UCLA}.* - \texttt{UCLA}.\mathtt{CS}.*$). What made it work is distributivity. When a difference expression intersects with a rule at the router, intersection distributes across the difference. Classes begin as differences and stay as differences; the tool scaled and ran on the Stanford backbone in seconds.

Later, when we described this to folks from formal methods, they looked embarrassed and told us that ternary algebras were well known in hardware verification, but had fallen out of favor compared to SAT solvers. While we were clearly naive, Peyman founded a company called Forward Networks, which uses his ternary algebra as a foundation. Perhaps this is because ternary algebra and difference compression are natural to networks with prefix and packet classification rules. We would not have found these domain-specific insights if we had used a model checker or SAT solver.

Shortly after my sabbatical, I joined Microsoft Research and met Nikolaj Bjørner. Nikolaj conceived of modifying his Datalog engine in Z3 to get all solutions to network reachability and recruited a terrific intern called Nuno Lopes. However, Nuno quickly found he had to add a difference of cubes data structure (and a new relational operator where he combined Select with Project) to get the engine to scale to what we called NoD (or Network Optimized Datalog). NoD is more flexible than HSA because it can easily be extended.

HSA and NoD scale using what one might call run-time dynamic equivalence classes. As packets move in the network, the equivalence classes are adjusted by adding a difference, removing null sets, etc. The Veriflow engine from UIUC used a clever idea that I call compile-time static equivalence classes. Before property checking, they used a trie-like structure to divide all possible network classes into equivalence classes. Unlike in HSA, these classes do not change at run-time.

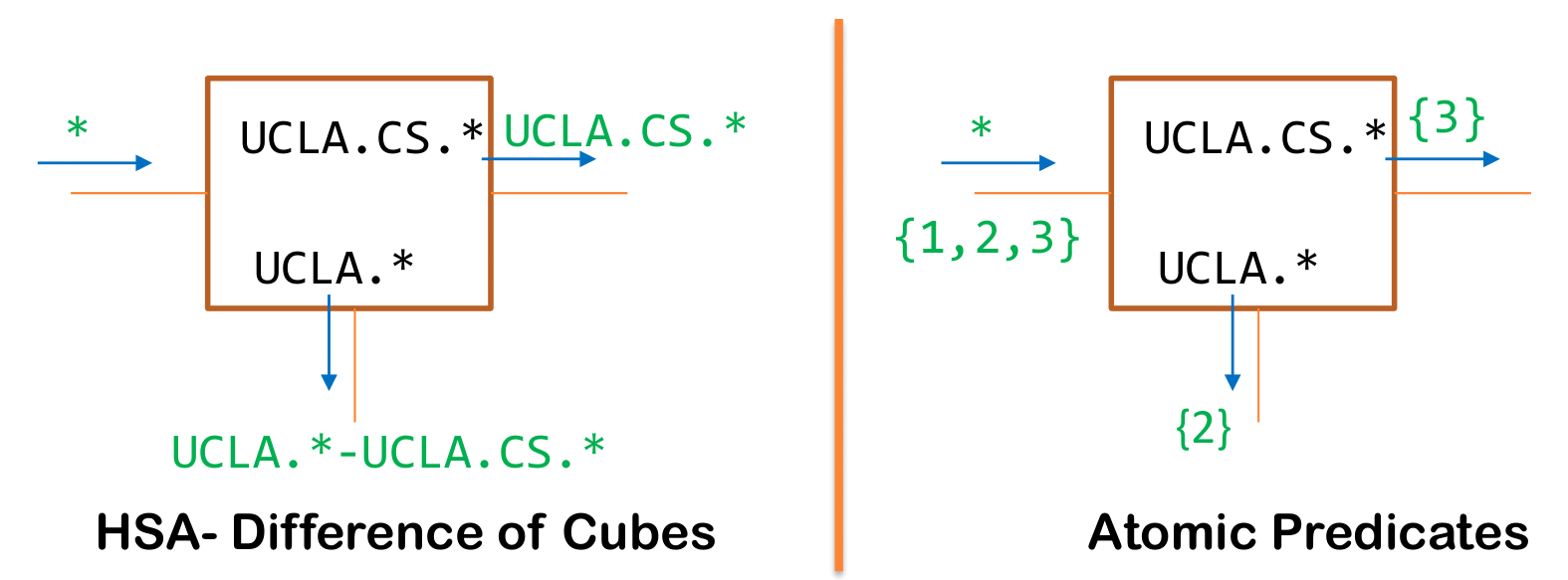

Veriflow was pioneering but perhaps a little ad hoc. The full fruition of this idea came with the Atomic Predicates paper by Yang and Lam. Consider a router with only $2$ forwarding entries for $\mathtt{UCLA}.*$ going to interface $I_1$ and $\mathtt{UCLA.CS}.*$ going to interface $I_2$ (see Figure). Header space analysis will compute all the differences in the wildcard expressions (e.g., $*- \mathtt{UCLA}$, which will be dropped, and $\mathtt{UCLA}.*$ - $\mathtt{UCLA.CS}.*$, which goes to $I_1$. These new expressions have to be matched at every subsequent router and then checked whether they are null, both expensive operations.

Instead, Atomic Predicates notices that there are three equivalence classes of packets, packets that match neither rule ($*-\mathtt{UCLA}.*$), packets that match the first entry, and not the second ($\mathtt{UCLA}.*- \mathtt{UCLA.CS}.*$) and packets that match only the third entry ($\mathtt{UCLA.CS}.*$). Each equivalence class is given a number ($1$, $2$, and $3$). The router rules are rewritten as $2 → I_1$, and $3→ I_2$. Reachability is computed by injecting the set of all packets from the source as the set $\{1, 2, 3\}$. Class $1$ gets dropped, class $2$ is forwarded to $I_1$, and Class $3$ is forwarded to $I_2$.

For a networking person, this is analogous to multi-protocol label switching (MPLS). We replace complex longest matching prefix and packet classification with integer labels that are set up before forwarding starts to make lookup faster. There are more details, but it comes closest to formally capture my students’ intuition as to why network verification should scale. The number of natural equivalence classes like $\mathtt{UCLA.CS}.*$ should be small.

Another insight from networking explains why atomic predicates work well. An early paper by Lakshman and Staliadis on packet classification showed that packet classification (ACL lookup) at a single router is equivalent to finding all hypercubes that match a point in a 5-dimensional space. There is a lower bound in computational geometry that shows that this geometric problem requires either large space or time. However, routers like Cisco’s CRS-1 use an algorithm called HyperCuts that work well in practice. Most networking people believe this is so because the number of disjoint geometric regions induced by a classifier are small in practice though they could be large in theory. The same reasoning explains why the number of atomic predicates even in a big network is quite small in practice.

There are other twists on equivalence classes. For example, at MSR, we observed that complex data centers had lots of backup links and routers that were essentially similar. While this is classically interpreted as symmetries in the state space, one can view the MSR work as defining equivalence classes on the topology; by contrast, Atomic predicates define equivalence classes on the headers.

Again this makes sense because the state for network reachability is a pair (packet, interface) where the packet is the current version of the header (which could be rewritten) and the interface is the interface in the network that the header packet is currently at while traveling from $S$ to $D$. While classical work in model checking looks for symmetries/equivalence class on the state space, in networks it makes sense to separately factor the equivalence of states into the equivalence of headers (Yang-Lam) and equivalence of interfaces. Later, Bonsai exploited symmetries for BGP routing, and Panda exploits symmetries in VMN to scale verification of stateful data planes like NAT.

So are we done? Far from it. First, most progress has been on the data plane. Ryan Beckett and collaborators have advanced the control plane, but Minesweeper does not scale to large networks. Stateful forwarding is still hard despite Panda’s work. But the bigger problem that remains even for dataplane verification is the lack of specifications. I will write about that in a post called “Look Ma, no specs” about some work to address this problem at UCLA.

There are other ways to reduce time to navigate large state spaces. We can use modularity as Todd Millstein points out where the state space is factored into smaller pieces, each with a smaller state space. Second, we can use abstraction: we transform the original network state space into a more abstract state space at the price of losing the ability to verify some properties. For example, Minesweeper abstracts away message passing of routing messages using solutions to the Stable Paths Problem. While modularity and abstraction are essential in other domains, perhaps precomputed equivalence classes are so successful in networks because networking is a shallower (not to mention finite) domain compared to programs or hardware.

I once described networking verification to Ed Clarke. His main question was: what is the state? (the (header, packet) pair described above). While I learned this is an essential question, I believe an equally important question to learn why a verification tool scales is: what are the natural equivalence classes for the domain, and how does the verification algorithm find them?

George Varghese

George Varghese