Alibaba has a global scale infrastructure to support its various types of online services (e.g. e-commerce, cloud computing, e-payment, etc.), which have more than one billion users in total. This infrastructure has O(10) core data centers, O(100) PoP (point of presence) nodes, O(1000) edge sites across 23 geographical regions, and 69 availability zones over North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania (see https://www.alibabacloud.com/global-locations).

Alibaba operates a private WAN (wide-area network) that interconnects all its data centers and peers with external ISPs around the world. The whole WAN has O(100) routers, which are from multiple vendors, and O(1000) links. Each router has O(1000) lines of configuration commands. There are also O(10, 000) IP prefixes announced over the WAN. With the fast growth of the application demands, our WAN doubles its scale every year and performs O(1000) update operations per month. In the coming 5G era, we expect the growth rate will be even higher given the massive demands on services from the edges that are closer to users.

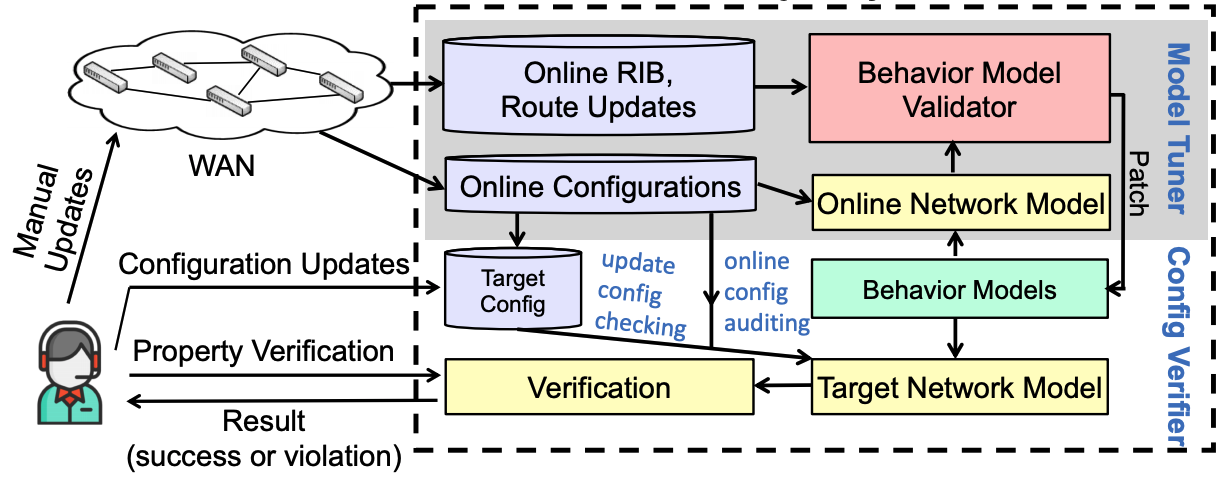

Since 2016, Alibaba starts to deploy network verification technologies inside its global WAN to fundamentally upgrade the way it enforces the reliability and efficiency of its network operations – never relying on human hands but computational logic. In this article, I want to share some of our refined experiences in deploying and using network verification techniques in the wild.

Motivation: why network verification?

Alibaba’s global WAN is a typical example of an extremely complex network that has to be operated and managed correctly. Since many applications rely on the WAN, an inadvertent mistake might result in severe incidents that impact millions of users and businesses. On the other hand, since the applications and businesses are quickly expanding and growing, the WAN has to frequently perform upgrades such as adding new devices, replacing existing devices with new models, adding new capacity and routes, adding new security policies, and so forth. The rapid evolvements of the WAN bring tremendous challenges to the protection of the network reliability:

-

The Opaque Network: Similar to many others, Alibaba’s WAN grows organically and incrementally by years with the demands and requirements from the upper-layer applications and businesses, such that it has massive “fait accompli”. A local design or a configuration left by one operator can easily become a legacy that her successor cannot fully understand or dare not change; An old device model might have some specific behaviors by default that some operators aware of but others do not. As a result, the consequences of a seemingly straightforward operation might trigger a hidden problem of a legacy, leading to disasters.

-

The Human’s Nature: Human beings are typically good at creativity, intuitions, and declarative expressions but poor at mastering enormous details, dependencies, and concurrencies mechanically and repeatedly. Therefore, it fundamentally deviates from human nature if we merely relying on human operators to operate the opaque and giant network and guarantee the reliability persistently. The problem is not too evident at the beginning of the Internet era because the network scale and complexity are way more limited than today, but it becomes imperative if we want the network to keep the pace of the applications and businesses.

-

The Loss of Experience and Knowledge: Relying on human beings to operate and protect the network has another essential drawback which is the lack of accumulation of experiences and knowledge on the network. Despite conceptually, all experiences for operating a specific network can be passed among operators via documents, but this way is super inefficient because documents can be inaccurate or incomplete, it requires tremendous effort from a person to learn and remember all the details, and information can be lost or distorted in the transitions among people. Hence, it is far from rigorous to use human’s nature languages to keep experiences and knowledge.

One can find that all of the preceding challenges originate from the fact that we entirely rely on human operators to accomplish a mission that is impossible to them. Hence, a road towards a brighter future is to rely on software to handle the details of the network operation and let humans focus on the high-level goals of the network. For instance, if a network device needs to be replaced by a new model and all connectivity remains the same during or after the upgrade, a human operator can tell the software to do that and the latter has the entire knowledge of the network and can accurately handle all details. People call this way “Intent-Based Networking (IBN)”, which is a magnificent future of network operation and management.

Network verification is an indispensable technology towards the ultimate goal of IBN, given that it provides a rigorous manner to check the correctness of network operations purely via software and mathematics. Alibaba is strongly motivated to adopt network verification as an automatic, rapid, and comprehensive way to (i) audit the current configuration snapshot for hidden errors; and (ii) check correctness and inconspicuous ambiguities of new configurations in an update.

Lessons: deploying network verification is not easy

Building a pragmatic and effective configuration verification tool on a large-scale and complex WAN like ours is not easy. Network verification is a promising technology, but it requires more considerations, other complementary techniques, or even a completely new design of the existing network verification methods to make it a real product and a practical tool that can be used by network operators who have zero background on formal verification and zero tolerates when the tool performs badly. Here we summarize some lessons and actions that must be taken to make network verification practical:

-

Accuracy. The first reaction when our operators heard the idea of network verification is asking the question “who verifies you?”. In research, we can say that let us assume the verification tools are correct, but it is very hard to realize in practice. The users (operators) will never trust this technology again if the verifier gives an incorrect answer and triggers a severe incident. Therefore, how to make a network verifier accurate on Day 1st after the deployment is a critical but difficult task to make this technology fly. Despite that we are still exploring better ways, our solutions to leverage ground truth in the running network [2] and other tools for cross-checking [3] are effective in practice.

-

Usability. A user of a verifier has to tell the tool “what to verify”, while from time to time we find it is not a trivial job. While academic people create a large number of languages to allow users to express their verification intents, no one, in reality, wants to learn a new and domain-specific language just for a specific purpose. On one hand, we must deeply understand the expressions operators want to make in their daily work; while on the other hand, we need to design an intuitive, declarative but also relatively constrained interface between human and the verifier. Currently, we have two solutions. First, we make everything into Python which is a de-facto favorite script language that is masted by most of the operators; Second, we design graphics interfaces instead of programming languages. Of course, we are still exploring better ways, such as natural languages. By the way, I found the blog site has already had an article talking about the same issue from an entrepreneur and an industry researcher who both have the same opinions from their practice (https://netverify.fun/network-verification-2-0/).

-

Scalability. It is a fundamental problem faced by all formal methods. It is also why verification’s deployment and usage are limited in general software correctness checking. Conceptually, people apply formal verification to the network logic in hoping to avoid the scalability drawback given that the network’s logic is constrained, but in our practice, it is usually not the case especially in networks such as a global WAN. If we holistically model the whole network with a single logic format, the running time of verification can rapidly ramp up to unacceptable (tens of hours) as the target network’s size increases. We do not aware of a generic solution to the scalability issue. A high-level principle we leverage multiple times is to introduce domain knowledge to break down a large logic format into multiple smaller pieces that significantly boost the speed of computation. For instance, in Jinjing[1], we only verify the “delta” of ACL updates rather than the whole ACL configurations; In Hoyan[2], we simulate the routing propagation process and prune the brunches early to shrink the final logical formulas; In Aquila[3], we take advantage of the fact that the P4’s pipeline is a DAG such that we use a topological sort to reduce the complexity with the number of states from exponential to linear. I believe there will be more methodologies in different scenarios. It is great to see many researchers working on this topic [6, 7].

Our work in Alibaba is majorly to solve the three problems in different scenarios. We found that how to practically put technology into use can lead to even more fundamental research in the technology itself [1,2,3], besides engineering efforts.

Prospect: the useability of network verification

Despite the current efforts, we found that we still have a long way to make network verification highly usable for a larger group of people. This is because the way how formal methods compute is different from how people think and work in daily life. For instance, in the beginning, operators strongly prefer network simulations or emulations (like CrystalNet[4]) just because these tools provide a command-line interface that is consistent with their and their existing scripts working environments. Most of the time, changing people’s habits and their existing toolchains is extremely hard. Therefore, how to make better usability of network verification technology is what we appeal to the whole community to pay attention to. It includes but not limited to the following aspects:

-

Familiar interfaces. It is critical to learn how operators’ preferences in their daily work and design a human-machine interface that is super friendly to network operators (some of whom might not be programmers). For instance, a verifier can also provide a command-line interface (showing the status of the routers) that is compatible with real routers.

-

Incremental verification. Most existing verifiers work on a snapshot of the entire network. However, in practice, most of the risks happen during updates. It will be a significant improvement in speed if one can perform incremental verifications – currently, one round of verification of an update can still take hours even if we have used many approaches to improve the verifier’s scalability. Also, it is desirable that the verifier can be general enough to identify the delta to verify instead of requiring the human to perform domain-specific analysis (e.g. Jinjing[1]). It is good to see people are talking about modularity in verification (https://netverify.fun/modular-verification-cna/, https://netverify.fun/toward-modular-network-verification/) and [5], which is a promising direction to solve the incremental verification problem.

-

Root-cause analysis. The strength of verification is the ability to catch all details and find potential errors or inconsistencies in the low-level logic. However, directly presenting the findings in the low-level details is very unfriendly to the users. Users demand that the verifier can also explain what happens in the low-level logic with very high-level and human-readable reasoning. For example, if the verifier finds an unexpected reachability issue, it should be able to trace back to the root cause in the configurations or designs, which is probably far away from the location of the reachability issue.

-

Intent learning from details. As mentioned above, a global WAN like Alibaba’s is also opaque in the overall intent of the whole network. The configurations in the network are accumulated over the years, and the intents of many of them have been unclear. Suppose we have an intent language to describe the network design, it is also interesting and important that we can convert the current network configurations to the declarative descriptions with the high-level intent language. Once it is done, incremental updates to the network will become much more controllable.

Conclusion

We devote ourselves to Alibaba to deploy network verification on our WAN because we believe it is a fundamentally new methodology to solve the tension between network growth and network reliability. However, it is far from straightforward to make this technique happen. Network verification is only mastered by a small group of people, so it has a long way to go to be widely accepted as a foundation in network operations. It brings both challenges and new research opportunities to us, and we hope you can jump into it and enjoy it!

References

[1] Tian, Bingchuan, Xinyi Zhang, Ennan Zhai, Hongqiang Harry Liu, Qiaobo Ye, Chunsheng Wang, Xin Wu et al. “Safely and automatically updating in-network ACL configurations with intent language.” In Proceedings of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, pp. 214-226. 2019.

[2] Ye, Fangdan, Da Yu, Ennan Zhai, Hongqiang Harry Liu, Bingchuan Tian, Qiaobo Ye, Chunsheng Wang et al. “Accuracy, Scalability, Coverage: A Practical Configuration Verifier on a Global WAN.” In Proceedings of the Annual conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication on the applications, technologies, architectures, and protocols for computer communication, pp. 599-614. 2020.

[3] Tian, Bingchuan, Jiaqi Gao, Mengqi Liu, Ennan Zhai, Yanqing Chen, Yu Zhou, Li Dai, Feng Yan, Mengjing Ma, Ming Tang, Jie Lu, Xionglie Wei, Hongqiang Harry Liu, Ming Zhang, Chen Tian, Minlan Yu et al. “Aquila: A Practically Usable Verification System for production-scale Programmable Data Planes.” In Proceedings of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, 2021.

[4] Liu, Hongqiang Harry, Yibo Zhu, Jitu Padhye, Jiaxin Cao, Sri Tallapragada, Nuno P. Lopes, Andrey Rybalchenko, Guohan Lu, and Lihua Yuan. “Crystalnet: Faithfully emulating large production networks.” In Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, pp. 599-613. 2017.

[5] Zhang, Peng, Yuhao Huang, Aaron Gember-Jacobson, Wenbo Shi, Xu Liu, Hongkun Yang, and Zhiqiang Zuo. “Incremental Network Configuration Verification.” In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks, pp. 81-87. 2020.

[6] Beckett, Ryan, Aarti Gupta, Ratul Mahajan, and David Walker. “Control plane compression.” In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, pp. 476-489. 2018.

[7] Plotkin, Gordon D., Nikolaj Bjørner, Nuno P. Lopes, Andrey Rybalchenko, and George Varghese. “Scaling network verification using symmetry and surgery.” ACM SIGPLAN Notices 51, no. 1 (2016): 69-83.

Hongqiang Harry Liu

Hongqiang Harry Liu