Recently, we have seen significant advances in tools that bring formal methods to networking. These tools verify if a given network satisfies important properties, automatically repair broken networks, and synthesize networks that provably satisfy properties. The hope is that these tools will help turn the practice of networking from a complex, potentially error-prone process to a principled discipline that is rooted in sound science and engineering, resulting in networks that are less bug-prone and, ideally, bug-free.

While we have made big intellectual strides in developing these tools, it still feels like the beginning of a long journey. In our view, the research community as a whole has a ways to go before the tools are useful and widely applicable. And a major reason is the lack of close interaction with the network operator community.

This article is a call to arms to those researching in this space to have a “network operator-buddy”, actually, several operator-buddies. Talk to these buddies about their needs and pain-points; talk to them about obtaining access to operational data, and let the data guide your research as much as possible; talk to them about your ideas, and get them to use your tools! Our experience has been that this opens up not only interesting new research problems but also a direct path to real-world impact. Such conversations can be especially valuable for newcomers to this space.

Below we outline some highlights from our own exploration of this research topic, and how it was, and continues to be, largely informed by feedback and help from network operators and by insights derived from their invaluable data.

How data, and conversations with operators, opened the door for us

Early work in this space focussed on network dataplane verification; notable examples include Anteater and HSA. These works aimed to validate if the current forwarding state of the network satisfies important properties, such as ensuring a given pair of hosts are blocked, and that there are no routing blockholes or forwarding loops.

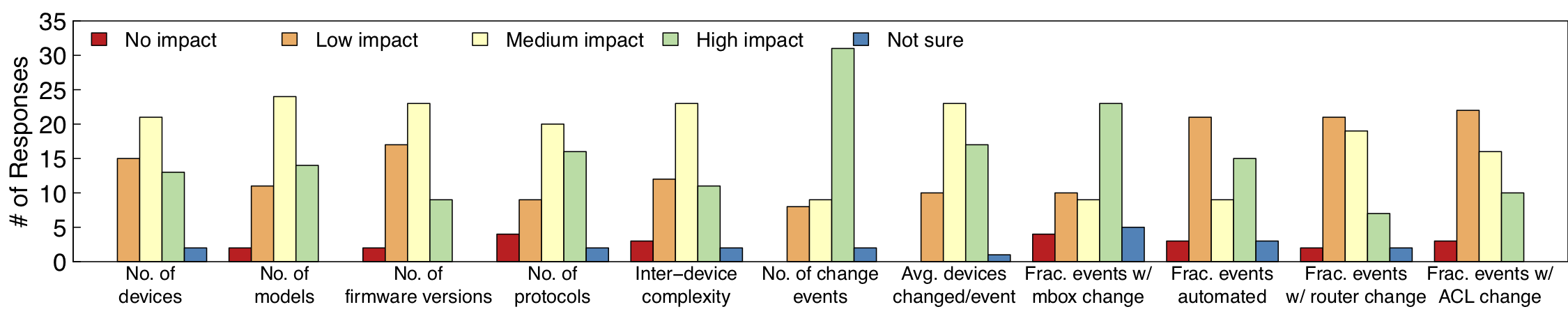

Around roughly that time, we were engaged in an empirical project on understanding operational management planes – how real-world networks are designed, and operated. To this end, we collected operational data (longitudinal network configurations, trouble tickets, topologies) from various networks around the US, including cloud data centers, enterprise networks, and university campus networks. (Data is also openly available from various research and education networks, including Internet2 and Purdue University.) A key component of this study was the frequency of configuration changes. Our study shed light on a surprisingly high frequency of change events, where each change event includes updates to configurations of multiple network devices close to each other in time. We found that change events can be of various scopes, some spanning an entire network, and others touch just a couple of devices.

Crucially, we found critical empirical evidence that networks with a greater degree of change – either frequent changes, or changes that are big in scope, or both – were more susceptible to failures (as indicated by higher incidence of trouble tickets). This in particular hinted at a potentially important use case that the state-of-the-art dataplane verification tools may be missing, namely, proactive verification. Dataplane verification tools verify just the current snapshot of the network’s forwarding state. Given the frequency of changes, and the relationship between changes and outages, we felt that network operators may also be interested in whether the modifications might result in violations of properties.

Our informal conversation with operators from US Big-10 schools (of which UW-Madison is one) confirmed this for us: operators indicate that they would much rather analyze configuration changes before deployment, rather than identify bugs when they manifest after deployment, by which time it is often already too late! About the same time, a group of researchers presented Batfish – the first control plane verifier to ``derive the actual data plane that would emerge given a configuration and environment.’’ Using Batfish, the researchers uncovered a variety of bugs in two real university networks.

Our own and others’ analysis of operational data and discussions with operators thus opened the door to our work on ARC and subsequently, Tiramisu, tools for proactive verification of network control planes.

More conversations helped us hone in on our approach

Early on when developing a framework for proactive control plane verification, our focus was largely on “one-shot” verification of properties, such as verifying if a given control plane configuration allows two hosts or subnets to reach each other, or that the configuration results in no routing blackholes. However, UW-Madison operators anecdotally mentioned several incidents where their network’s configurations appeared safe (i.e., passed various simplistic tests) prior to rollout, but the network nevertheless experienced major service outages under unexpected but routine events such as a link or a switch failure. These anecdotes highlighted for us the importance of analyzing a control plane’s ability to satisfy key properties under various possible failure scenarios, i.e., being able to answer questions such as: does this configuration change continue to ensure reachability between a given pair of subnets even when an arbitrary set of k links fails unexpectedly?

This observation led to a major change in our approach to verification: we were initially exploring a simulation based approach (similar to Batfish) where we would execute a control plane’s processing to determine what paths it might end up generating, but such an approach becomes quickly untenable when exploring the large number of failure scenarios – running a simulation (which is already slow) per failure scenario is prohibitively expensive. We then pivoted to develop a control plane model that is amenable to rapid simultaneous exploration of many failure scenarios. The result was ARC, a first-of-a-kind graph based control plane encoding. ARC allows mapping the problem of proactively verifying if a control plane satisfies a given property under failures (e.g., “k-reachability” as exemplified above) to running appropriate fast, polynomial time graph algorithms (e.g., determining if the graph min-cut > k).

In trying to enable fast analysis under failures, ARC makes some assumptions about the control plane’s design. For example, it assumes that routing protocols such as BGP are used in specific ways (such as, no community attributes, and no iBGP), and layer-2 (e.g., VLAN) configurations are correct. Talking to operators from NYSERNET, ESnet, UW-Madison, and Colgate University, showed us that these assumptions are quite limiting in practice and hinder ARC’s applicability. Analyzing the configuration data from some of these networks further showed the broad extent to which the protocol features we “assumed away” were in use. This analysis led us to Tiramisu, our most recent verification tool; Tiramisu’s control plane embedding builds off of ARC’s simple graph model. Notably, Tiramisu uses a multi-layer graph to encode inter-protocol dependencies (e.g., dependencies between BGP and IGPs, and routing protocols dependence on layer-2 technologies like VLANs), and multi-dimensional edge attributes to encode the various metrics routing protocols use in their decision-making. (Stay tuned for a future article where we hope to cover Tiramisu’s technical underpinnings in more detail!)

Identifying new directions

Operators continue to offer us valuable insights on our verification tools that have steered our work in an interesting new direction, and helped us identify which problems are the most important to work on.

Notably, at a presentation on ARC and Tiramisu at a large online service provider, a network operator asked us if the graph-based control plane abstractions underlying these tools can be used to validate if a given network is susceptible to overload: more precisely, does there exist a combination of a group of links failing and a network traffic matrix that causes the network’s control plane to select paths that may overload certain links? This is an example of a “quantitative verification question” that existing proactive verification tools cannot answer because of their exclusive focus on qualitative path properties (such as path existence, number of paths, etc). Interestingly, the same question arose in a discussion we had with operators at UW-Madison. This led to our work on QARC, a tool for exhaustively checking networks for potential susceptibilities to overload. We hope to talk about QARC at length in a future article.

Our work on control plane repair and synthesis – yet another topic we hope to explore in a future article – were also both heavily influenced by surveys of network operators, analysis of operational data, and, of course, conversations and interviews with operators.

How to make operator-buddies?

As our experience illustrates, operator-buddies can be an invaluable resource. They can help understand what problems to focus on, identify how to refine candidate approaches, and also suggest new directions altogether. But how does one (especially someone in an academic setting) go about making operator-buddies?

Luckily in our experience there are plenty of avenues for building relationships with network operators.

First, consider setting up a coffee meeting or two with your campus operators. You will be surprised at how readily willing they are to meet, talk about their operational practices and pain points, and also share data! (If they are hesitant to share raw data with you, you can ask if they could share configurations that have been anonymized using tools like Netconan.) Once you have built a sufficiently close relationship, your campus operators may also be willing to introduce you to their friends from other regional schools or networks who themselves may contribute more discussion or even data.

Also, consider spending time in the industry, e.g., as part of an year-long sabbatical or summer internship, and work closely with network operators there. You will likely obtain access to data while employed there and you may lose access when you leave, but the insights you gather will stay with you and inform your work for years to come.

Finally, consider attending network operator events such as NANOG and CHI-NOG, or conferences co-located with events such as the Open Networking Summit and IETF meetings, and setting up conversations with network operators there. These events attract people running a very broad variety of networks, campuses, enterprises, ISPs of various sizes, and cloud operators, giving you perhaps the broadest exposure to your ideas and the broadest possible net for your to rope in operator collaboration. Being a passive observer of the discussions within these groups can also be insightful, so sign-up for their mailing lists.

Or, drop us a note! We would be happy to put you in touch with our local operator-buddies and you can take it from there!

Aditya Akella

Aditya Akella  Aaron Gember-Jacobson

Aaron Gember-Jacobson