Verification and synthesis are old problems in computer science. Verification seeks to answer the question: “can any input to a program result in that program producing an incorrect output.” Likewise, synthesis seeks to answer the question: “can I generate a program that produces the correct output for every input.”

The motivation for verification and synthesis comes from the practical realization that humans often make mistakes and commonly introduce bugs into their systems. Having a way automatically (and quickly) find/fix all bugs in a system is highly appealing, particularly when such systems become sufficiently complex.

While traditionally researchers have developed formal methods to verify computer hardware and software, recent trends in networking have exacerbated the need for such methods for networks as well. For example, the rise of cloud networking powered by the creation of enormous data center networks has dramatically raised the operational complexity of those networks. At the same time, as more services move online, it has become more vital that networks be bug-free and reliable.

In response, researchers have started exploring the use of formal methods for networking. While they have made substantial progress on some problems, others remain unsolved.

This article presents our view of the state of research on network verification. One category of work in this space aims to prove that network devices implement their functionality correctly (e.g., NICE and Dobrescu et al.). Another category aims to prove that the behavior of a given network is as intended by the operators. It typically assumes that the network devices are operating correctly; unintented network behavior can emerge even if all devices are bug-free when the network is not configured correctly. We will focus on the second category of work because the first one is closer to general software verification, and it is in the latter category where a lot of progress has been made recently. We will focus on first category of network verification and on network synthesis in future articles.

The perspective in this article is shaped by our research and a course we taught that coalesced the ideas in this space. (We thank our collaborators and students for all we have learned from them.) We realize that our perspective is inherently biased and incomplete and that we risk irking research colleagues who do not agree with our characterization (or whose work we failed to include). We invite those researchers to share their own perspectives.

The first wave: Data plane verification

Some of the earliest work on network verification was adopted for network “data planes”. The data plane refers to the part of the network responsible for forwarding packets from point A to point B. In general, network forwarding is performed by a collection of “switches” that each maintain a forwarding table that matches a packet entering the switch and determines which port(s) the packet should go out of.

The matching mechanism depends on the network. Traditional routers match packets based on the longest matching prefix, yet newer technologies such as OpenFlow and P4 allow for more general packet matching. In addition, routers along the path may even transform or encapsulate/decapsulate packets.

Data plane verification aims to prove properties like node A cannot reach B, independent of the packet headers it chooses; node A can reach B; or no packet in network will loop. The challenge is to provide such guarantees for all possible packet headers (of which there are tens of billions). This challenge gets harder in the presence of packet transformations and encapsulations because those operations change the headers.

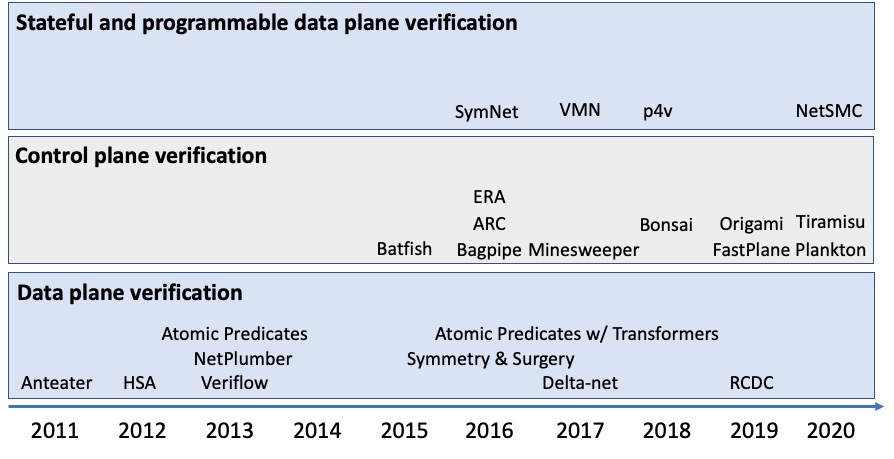

Drawing on basic verification tools invented originally for other domains, networking researchers have developed a range of approaches to tractably reason about all possible packet headers. Some of the first data plane verification work encoded network forwarding tables and properties of interest as SAT constraints. The SAT solver’s declaration that constraints are unsatisfiable or the satisfying variable assignments indicated if the property held for the network. This approach was first outlined by Xie et al. and then shown to work on real networks in Anteater.

Header Space Analysis used ternary simulation to efficiently propagate the set of all possible packets through the forwarding tables to find where every input packet will end up. This approach scaled better and it could identify all possible packets that violated a property, where the SAT-based approach identified only one counterexample.

Later approaches to data plane verification improved upon Anteater and HSA in one dimension or another, such as

- making the analysis incremental (e.g., Veriflow, NetPlumber, Delta-net);

- making the analysis faster by identifying equivalence classes of packet (e.g., Atomic Predicates;

- making the analysis faster identifying equivalences across parts of the network (e.g., Symmetry and Surgery;

- decomposing (some) global properties into local properties (e.g., RCDC).

The second wave: Control plane verification

While data plane verification involves analyzing how packets are forwarded according to the tables present at every switch, in real networks these tables are themselves populated by other protocols or software, known as the “control plane” of the network. The appeal of analyzing the control plane is that it can help prove the correctness of network behavior proactively, before that behavior emerges in the network.

Network control planes typically come in two flavors: (1) distributed routing protocols, or (2) a centralized orchestrator. Since the centralized orchestrator is typically written in a general purpose programming language, traditional software verification techniques such as those based on Hoare Logic apply. However, automatically verifying arbitrary software is undecidable in general, and highly challenging in practice.

As a result, arguably, researchers have had more success with (1). For example, Batfish simulates the protocols to their fixed points, which produces the forwarding tables, and it then leverages data plane verification tools to check for various kinds of bugs.

Such simulations, however, can only explore one fixed point, and any environmental changes such as a link failure or an external route advertisement requires re-executing the simulation. This limitation makes it intractable to prove correctness for arbitrary changes. Minesweeper and BagPipe encode the fixed-point of distributed protocols as a function of the network environment using SMT. They can then use SMT solvers like Z3 to search for a network environment, such as a combination of failures, that will result in undesirable forwarding behavior. However, these tools are significantly less scalable than Batfish.

As with data plane verification, later work improves control plane analysis along one dimension or another, such as

- making the analysis faster using custom graph encodings for the fixed point (e.g., ARC, Tiramisu);

- improving simulation speed for networks with monotonic control planes (e.g., FastPlane;

- using explicit-state model checking to explore a range of environments (e.g., Plankton)

- making the analysis faster by identifying equivalences across parts of the network (e.g., Bonsai, Origami);

- making the analysis faster by using abstract interpretation (e.g., ShapeShifter)

The third wave: Stateful and programmable data planes

The first wave of data plane verification work largely tackled “stateless” dataplanes where how a packet was treated did not depend on prior packets. However, not all network data planes adhere to this model. A network could have middleboxes that perform stateful packet processing, such as denial-of-service protection logic that is based on all packets seen in the recent past. Additionally, an emerging class of devices allow for “programmable” dataplanes (e.g., Barefoot Tofino), where network engineers can flexibly define how packets are processed. These capabilities of network devices enable exciting new functionalities and promise to allow networks to evolve more quickly. However, they also make verification more challenging since the data plane can now perform complex logic.

Work that tackles such data planes is in its infancy, but as with stateless dataplane verification, researchers are exploring different verification approaches. Two of the early works, VMN and SymNet, employed symbolic execution and SMT encoding respectively for verifying dataplanes with middleboxes. More recently, NetSMC used model checking for this domain.

An important effort in the domain of programmable dataplace is p4v, which leverages verification condition generation to reason about such programs with assumptions about the control plane. Fortunately, the absence of loops or recursion in data plane programs (since they must forward at line-rate) allows tools like p4v to be fully automatic.

So what problems have been solved?

Perhaps the most clearly “solved” problem in network verification is that of stateless data plane verification, which also happens to be the earliest work in this space. Stateless data plane verification tools today can already scale to handle large networks with millions of forwarding table rules and thousands of routers, all at human time scales. Further work in this area has also revealed additional optimizations that make such tools even more scalable. These tools have been successful enough to find their way into practical use at large cloud providers such as Amazon and Microsoft and offered commercially by startups such as Forward Networks, Intentionet, and Veriflow.

Control plane verification of individual network fixed-points is also a solved problem. Tools such as Batfish and FastPlane can quickly compute and verify the fixed point for large networks. This approach too is in production use at companies such as Microsoft and offered commercially by Intentionet.

So what problems remain open?

Although verifying stateless data planes is largely a solved problem, the closely related problem of verifying stateful and programmable data planes is unsolved. The early work in the domain of middlebox proccessing is promising but many difficult problems related to scale and realism are not fully solved. Similarly, for programmable networks, while p4v can verify the forwarding functionality of a single switch, it is not possible to verify the correctness of an entire network of programmable switches. Given that many use cases for programmable switches require coordination, this is an important next step. Even further away is the possibility of jointly verifying both the control and data planes for networks with programmable devices. Such a joint analysis is promising because it could reduce the specification annotation burden on users (as required by p4v) since control plane invariants could be learned directly instead of inferred.

Control plane verification for a range of fixed points, while possible today, remains challenging to scale to large networks. Recent works such as Plankton and Tiramisu have made reasoning about failures more scalable, but reasoning about route advertisements from other networks remains problematic. For the latter, Minesweeper and BagPipe are the only tools capable of such reasoning, but they do not scale beyond a few hundred devices. One could speculate if reasoning about arbitrary external route advertisements is worth the additional complication. For many networks, these routes may be known or highly constrained. For other networks, a practical approach may be to verify which routes a network allows in as a precondition.

Summary

Network verification is a timely research area that holds the promise of increasing the reliability of critical network infrastructure. Researchers have made rapid strides over the last decade, with ideas already deployed in the world’s largest networks. Several problems remain, however, and we look forward to the research and engineering communities addressing them effectively over the next few years.

Ryan Beckett

Ryan Beckett  Ratul Mahajan

Ratul Mahajan