Networks routinely need changes to patch security holes, expand capacity, perform routine maintenance, and a myriad of other reasons. But every change is dangerous, and brings with it the risk of an outage. In theory, network verification can prevent a range of outages, but in practice, it often falls short, and outages have occurred in networks that are using verification.

The main reason is that the network verification effort is only as good as the specification being verified, and most networks do not have good specifications. Indeed, because most networks have been built up, extended, and fixed over time, by multiple teams of engineers, no one really knows how or why they work in detail. To the extent the how and why is known, it is typically not written down anywhere precisely, for easy use as a specification.

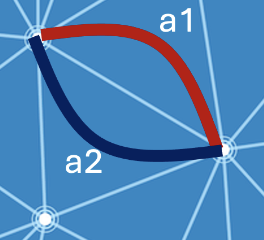

Consider a common change: Move all traffic on link a1 to a parallel link a2 as a precursor to shutting a1 for maintenance. Here’s a first picture of the setting. Traffic on the red link before the change should flow along the black link after the change.

To check that our change is correct, one should verify that a1 no longer carries any traffic and that all traffic it was carrying moves to a2. Doesn’t sound too hard! But that’s just the beginning—the easy part really.

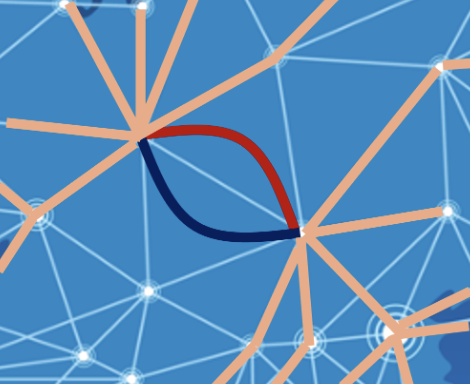

We also do not want to change how traffic flows upstream of a1 and a2 and we do not want to change how traffic flows downstream of a1 and a2. The following picture gives us a better perspective on what we need to ensure—traffic on the orange subpaths must remain unchanged.

However, that is not all. We should also ensure that traffic flowing across other links in the network (such as the traffic traversing green links below) is unaffected.

In other words, to craft a specification that captures the full intent of the change, it seems as though we will need to specify how all traffic moves through the network, exactly. In large networks, which may have millions of traffic classes, such specifications are nearly impossible to come by. Even if we had such a spec, it would be complex, difficult to understand, and a significant effort to maintain. Partial (coarse) specifications do sometimes exist, but they only provide partial protection.

Can we verify network changes without such complex behavior specifications? This may seem impossible at first sight, but our recent work points to a path forward. The key idea is to use relational verification—instead of reasoning about a single network snapshot in isolation (say, the post-change network snapshot, as is typically done today), reason jointly about two snapshots, the pre- and post-change snapshots.

A relational specification describes similarities and differences between snapshots. For example, “Path1 is the same as Path2” is a relational specification as is “Path1 changes to Path2.” If the impact of changes is small, and most of the network is supposed to stay the same, then relational specifications can be concise, even if the network itself is enormous. Fortunately, our experience is that real-world changes are usually quite small and relational specs are quite manageable.

To experiment with these ideas, we have developed a language called Rela for writing relational specifications, and an automated verification procedure to check that networks adhere to them. Consider again our example from above: We want traffic using link a1 to now use link a2. The core of such a change is a one-liner in Rela:

spec change_link = { a1 : replace(a1, a2); }

The first occurrence of a1 is called the “zone” (or area of interest) of a change. Zones are sets of paths through the network. They are specified using regular expressions. The command after the colon is a traffic modifier. In this case, the modifier states that traffic running through a1 should instead run through a2.

If we would like to say that some part of the network does not change, that is easy too. Here is a specification that says all paths (regular expression .* ) stay the same (the preserve modifier). Sometimes engineers will re-factor a configuration; a specification like this checks that they did not accidentally change network forwarding paths.

spec nochange = { .* : preserve }

To extend the specification from our example to express that upstream and downstream subpaths do not change, we extend the zone of the specification and require that those parts do not change (the semicolon concatenates specifications along a set of paths):

spec change = {

nochange;

change_link;

nochange;

}

Finally, to specify that traffic that has nothing to do with link a1 also remains unchanged, we use the prioritized choice operator » denoting that the second term applies only to paths that are not covered by the first term. The full specification of our change is:

spec fullchange = change >> nochange

These two terms, none of which require the engineers to know much about the current network behavior, represent the complete specification of the change. Based on this specification, any unintended behavioral change (e.g., due to a buggy configuration change) will be flagged by Rela.

See the paper for other types of specifications including more path modifiers and mechanisms for specifying different changes for different kinds of packets separately. The paper also explains how we verify such specifications using finite state automata and transducers. Our experiments show that Rela is expressive enough to describe over 9 in 10 complex changes to a large cloud provider’s backbone network in fewer than 10 lines and verification takes under 20 minutes even though the network has over a thousand of devices.

We believe that relational reasoning about networks has immense potential, and change verification is just one application of many. Relational reasoning could also verify differences between parts of the network that are expected to be similar but not identical (as is common for large networks), and it could also help synthesize configuration changes from specifications. We are excited about exploring such applications in the future.

Images courtersy of Network Map Vectors by Vecteezy

Zachary Kincaid

Zachary Kincaid  Arvind Krishnamurthy

Arvind Krishnamurthy  Ratul Mahajan

Ratul Mahajan  David Walker

David Walker  Xieyang Xu

Xieyang Xu  Yifei Yuan

Yifei Yuan  Ennan Zhai

Ennan Zhai